Archaeology and paleontology are like two puzzle pieces of the past—each uniquely shaped, yet crucial to understanding the bigger picture of history. Despite their distinct roles, these fields often find themselves tangled in the web of public confusion. After all, they both involve digging into the ground, uncovering ancient mysteries, and using fancy tools that make the rest of us feel underprepared for a camping trip. But is archaeology a paleontology? Not quite.

Is Archaeology A Paleontology?

What Is Archaeology?

Archaeology, in its simplest form, is the study of human history and culture through material remains. This field dates back centuries, with early archaeologists hunting for treasures and clues about lost civilizations. Today, however, archaeology is a highly scientific discipline that prioritizes preservation over treasure hunting.

Definition of Archaeology

The word archaeology comes from the Greek roots “archaios” (ancient) and “logos” (study), literally meaning “the study of the ancient.” Archaeologists are history detectives, examining everything from tools, pottery, and ruins to ancient garbage heaps. Yes, trash is a goldmine for archaeologists—it tells stories about diets, habits, and trade.

Archaeology’s primary goal is to piece together the story of human development. For instance, what tools did our ancestors use to survive? How did they build their homes? What were their rituals and beliefs? By answering these questions, archaeologists help us connect with our shared human heritage.

Scope of Archaeology

The scope of archaeology is vast, encompassing:

- Artifacts: Portable objects, like tools, weapons, jewelry, or pottery.

- Features: Non-portable evidence, such as hearths, postholes, and buildings.

- Ecofacts: Natural remains, like seeds or animal bones, that provide clues about ancient environments.

- Cultural Landscapes: Entire areas altered by human activity, such as terraced fields or ancient cities.

Archaeologists rely on a mix of tools and methods. For example, carbon dating helps determine the age of organic materials, while ground-penetrating radar maps out hidden structures without digging. From exploring ancient Egyptian tombs to uncovering Viking settlements in Greenland, archaeology is as diverse as the cultures it studies.

What Is Paleontology?

If archaeology is the study of humans and their past, paleontology takes a step further back in time—millions, even billions of years—to study life itself. From dinosaurs to prehistoric plants, paleontology is all about uncovering the secrets of ancient ecosystems and the organisms that once thrived on Earth.

Definition of Paleontology

The term paleontology comes from the Greek words “palaios” (ancient), “ontos” (being), and “logos” (study), meaning “the study of ancient life.” Paleontologists are nature’s historians, focusing on fossils to piece together the story of evolution, extinction, and environmental changes over geologic time. Unlike archaeologists, paleontologists are far less interested in human-made objects and more fascinated by the natural world—think trilobites, mammoths, and yes, everyone’s favourite: dinosaurs.

But paleontology isn’t just about dinosaurs. It includes the study of plants (paleobotany), microscopic organisms (micropaleontology), and even ancient climates (paleoclimatology). These subfields help scientists understand how life adapted—or didn’t—to environmental shifts.

Scope of Paleontology

The scope of paleontology is as massive as the creatures it studies. Here’s what it typically involves:

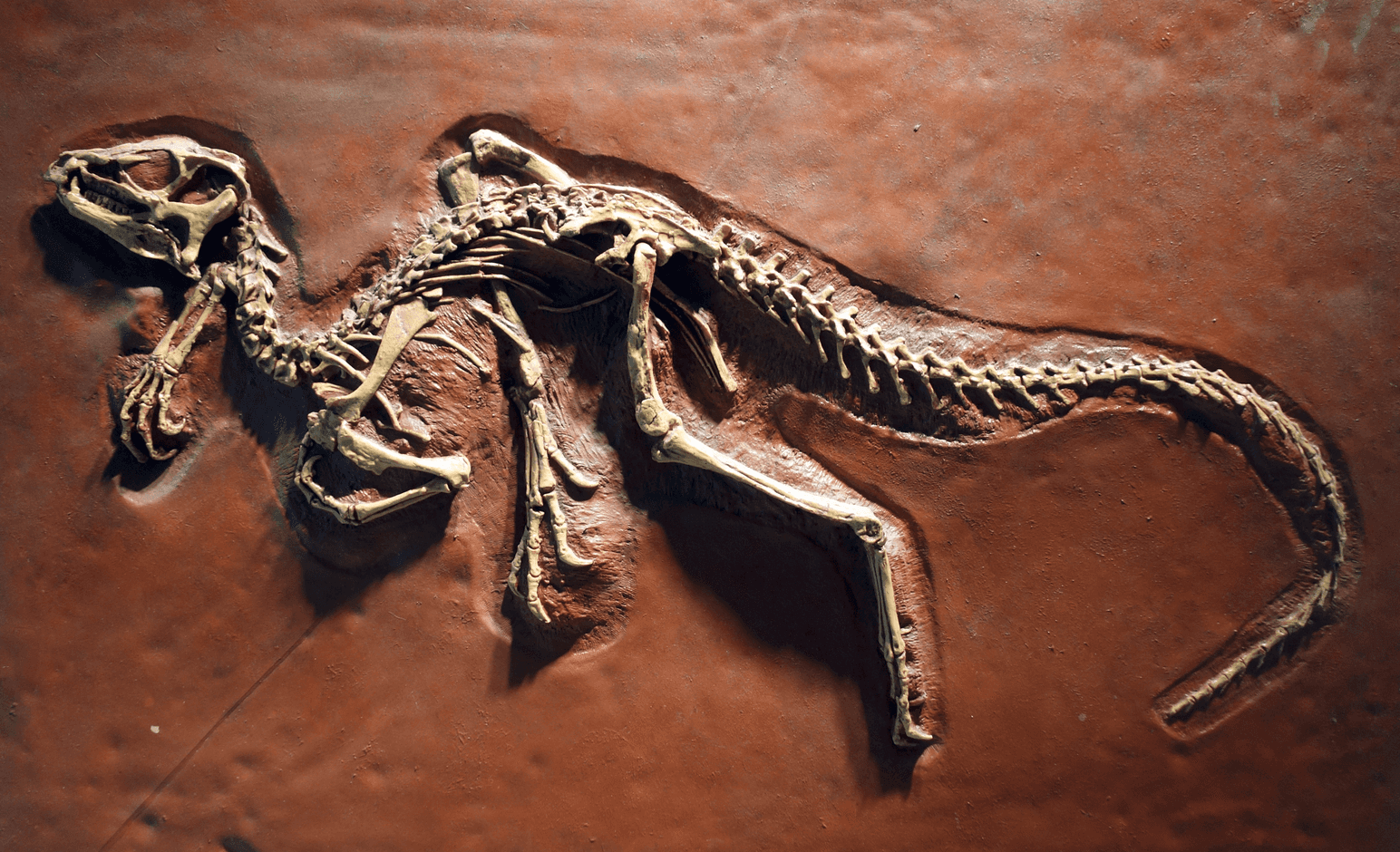

- Fossils: Remains or traces of ancient organisms, such as bones, shells, and imprints.

- Geological Context: Layers of rock that reveal the Earth’s timeline.

- Ecosystems: Ancient habitats reconstructed through fossil evidence.

- Evolutionary Patterns: How species evolved, diversified, or went extinct over time.

Paleontologists use specialized tools like chisels, rock hammers, and delicate brushes to extract fossils without damaging them. They also rely heavily on laboratory analysis, such as CT scanning, to examine internal structures.

Take, for instance, the groundbreaking discovery of Archaeopteryx, a feathered dinosaur that revealed the link between birds and dinosaurs. Or consider the study of prehistoric marine fossils, which has provided crucial insights into how climate changes impacted ancient oceans.

Paleontology’s findings aren’t just academic—they help predict the future. By studying how species responded to past climate shifts, scientists can make better guesses about what might happen in a warming world.

How Are Archaeology and Paleontology Similar?

At first glance, it’s easy to see why people lump archaeology and paleontology together. Both involve digging into the earth to uncover long-lost pieces of the past, and both rely on similar scientific techniques to date their findings. But the shared surface-level similarities only scratch the surface.

Common Ground Between the Two Fields

Here’s how archaeology and paleontology overlap:

- Study of the Past: Both fields aim to reconstruct history—archaeologists focus on human history, while paleontologists delve into the natural history of life on Earth.

- Excavation: Digging is a cornerstone of both disciplines. Whether it’s an ancient burial site or a fossil bed, both rely on uncovering material evidence buried underground.

- Dating Techniques: Methods like radiocarbon dating, stratigraphy (studying rock layers), and dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) are used to establish the age of findings.

- Preservation of Evidence: Both professions require careful handling of delicate remains, whether it’s a clay pot or a fossilized ammonite.

Overlapping Areas

There are times when the two disciplines directly intersect, creating a unique collaborative space. One example is prehistoric archaeology, which focuses on human history before written records. In these cases, archaeologists often study early human fossils—a realm where paleontology and archaeology overlap.

For example, the famous discovery of Homo naledi in South Africa’s Rising Star Cave system involved archaeologists and paleontologists working side by side. This collaborative effort revealed not only the physical traits of an early human ancestor but also clues about their behaviors and burial practices.

Another overlap occurs in paleoarchaeology, a subfield that studies the interaction between ancient humans and their environments. Fossilized remains of extinct animals—like mammoths or saber-toothed cats—found alongside human tools can shed light on hunting practices or ecological impacts.

Fun Fact:

Did you know? The oldest tools ever discovered, made by early humans around 3.3 million years ago, were found in Kenya—and these tools predate Homo sapiens! While this is primarily archaeology, it hints at the broader evolutionary context, which paleontology often helps to decipher.

Key Differences Between Archaeology and Paleontology

Despite their shared methodologies and occasional overlaps, archaeology and paleontology are fundamentally different in their focus, scope, and approach. Understanding these differences is crucial to appreciating the unique contributions each field makes to our understanding of the past.

Focus of Study

The core distinction lies in what each field studies:

- Archaeology: Archaeologists study human history and culture. Their work revolves around artifacts, structures, and other physical remnants that shed light on how people lived, what they believed, and how societies evolved. For example, an archaeologist might analyze ancient pottery to understand trade networks in the Roman Empire.

- Paleontology: Paleontologists focus on life forms that predate humans or existed alongside early humans. They study fossils to understand evolutionary history and ancient ecosystems. For instance, a paleontologist might examine the fossilized remains of a giant sloth to determine its habitat and diet during the Ice Age.

Think of it this way: if an artifact shows human influence (like a spearhead), it’s archaeology; if it’s purely natural (like a trilobite fossil), it’s paleontology.

Chronological Scope

The timeline of each field also sets them apart:

- Archaeology: Typically deals with the last 2.5 million years, covering the span of human existence. This includes everything from early stone tools to 20th-century artifacts, like items from World War II battlefields.

- Paleontology: Looks much further back, covering the entire history of life on Earth, which stretches over 3.5 billion years. Paleontology examines everything from the first single-celled organisms to the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs.

For example:

| Discipline | Time Period | Examples of Study |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeology | Last 2.5 million years | Ancient cities, pottery, tools |

| Paleontology | 3.5 billion years ago–now | Dinosaurs, mammoths, fossil plants |

Methodologies and Tools

Although archaeologists and paleontologists both dig into the earth, their techniques and tools vary depending on their goals:

- Archaeological Methods: Archaeologists often use tools like trowels, brushes, and ground-penetrating radar to carefully uncover and map human-related sites. They focus on context—how artifacts are arranged within a site can reveal crucial details about the people who lived there.

- Paleontological Methods: Paleontologists use more rugged tools, like rock hammers and chisels, to extract fossils embedded in sedimentary rock. They frequently work with geologists to understand the layers of rock (strata) that fossils are found in, which helps determine their age.

One field prioritizes cultural context, while the other seeks biological and ecological context.

Case Study: The Great Mammoth Debate

Sometimes, the differences become a little blurry. Take mammoths as an example:

- When studying mammoth bones to understand their diet, habitat, and extinction, you’re in paleontology territory.

- If you discover a mammoth skeleton alongside human-made tools or evidence of hunting, this shifts into archaeology. It’s now a question of how humans interacted with these creatures, not just the creatures themselves.

This distinction ensures that each field focuses on its strengths while contributing to a broader understanding of the past.